You

probably haven't noticed since it hasn't really been mentioned in the

news or on social media, but Star Wars: The Force Awakens recently

hit theatres. Plenty have been showing Star Wars and only Star Wars

for several weeks running. They are going to make a lot of money.

Meanwhile, I, a longtime Gundam fan, am currently watching the

original Mobile Suit Gundam for the first time. For its age, it's an

incredible show; the quality of the animation is astounding, and the

story is pretty timeless. Still, I can't help but notice that it came

out in 1979. Know what else came out just two years earlier? The

original Star Wars.

Creating

the “space” genre, or merely repackaging it?

A

lot of the Star Wars pre-game analyses I saw in the weeks leading up

to the new film's release claim that Star Wars launched the space

genre. Before Star Wars, commercially viable, intellectually

accessible science fiction simply did not exist.

Bullshit.

I'm

not just saying that because of Gundam. Gundam launched after, not

before. I just explained that like two paragraphs ago. Jesus, please

try to pay attention. No, I'm alluding to something interesting I

read in a recent Cracked article:

“George Lucas, hot off the enormously successful American Graffiti, tried to buy the rights to Flash Gordon to turn it into a big-budget film franchise. They couldn't come to terms on a deal, so Lucas just decided to just write his own version. That's all it was. ... The rough draft of Star Wars was an incoherent rambling mess, borrowing entire scenes from other movies, mostly Akira Kurosawa samurai films (then again, Kurosawa had borrowed his from American Westerns). ... For the space dogfight that would mark the climactic battle at the end of the film, Lucas literally stitched together footage from war movies and documentaries, then just re-filmed them with spaceship models, shot for shot. In other words, Santa Claus isn't real."

|

| Space Captain Harlock |

Flash

Gordon, "Buck Rodgers, Kurosawa, Westerns (Tattooine!), old WW2 footage. Sounds

like Lucas had a lot of good material to draw on. But don't think

that Japan was devoid of material at this point, either! It had its

own “swashbuckling space adventure,” the 1970s anime Space

Captain Harlock. It was popular enough to merit a revival a couple of

years ago. And there's plenty more where that came from. 2001: A

Space Odyssey, both book and movie. Or how about The War of the

Worlds, an HG Wells story from fucking 1897. The decade preceding

Star Wars even saw the rise of another space-themed series of TV

shows and movies, an obscure property called “Star Trek.”

|

| Metal Gear REX |

Everything

new steals from everything old. Harry Potter draws on centuries of

mythology. Divergent mashes up Harry Potter and The Hunger Games,

which in turn probably took ideas from Battle Royale. Metal Gear is a

mixture of old movies, whatever is currently on Kojima's mind, and,

inevitably, Gundam, because you can't tell me the series that

launched the mecha subgenre did not in some way influence the

eponymous war machines. Hell, even Gundam itself mercilessly

cannibalizes its own plotlines to new purpose. Gundam Seed is just a

repackaged Mobile Suit Gundam; 00 is just Wing for a post-9/11

audience.

Neither

franchise “created” the space adventure. That door had already

been slowly dilating open for decades. What they did

was put an interesting spin on established conventions and make their

own contributions to the cultural landscape. Which, given the flood

of boring, derivative fluff we're inundated with every day of every

year, is a huge accomplishment anyway.

Legacy

|

| A steam-powered Oobu machine from Sakura Taisen. This one in particular is piloted by the character Sakura. |

Supposedly,

less than 1% of people (English speakers?) have never seen any of the

Star Wars movies. I was actually surprised it was that high! That's

the power that these movies have. And besides Dragonball Z and

Pokemon (in that order), I can't think of any other cultural treasure

that has had a stronger or more enduring impact on the modern

Japanese popular consciousness than Gundam. Final Fantasy? In Japan,

Dragon Quest is bigger. Dragon Quest? Nice try, you sarcastic twit,

because Dragon Quest is kind of only for nerds, while the other three

are widely known by everyone. Sakura Taisen? You know what, now

you're just annoying me.

I've

heard that when making Sonic 2, Naka Yuuji wanted to pay tribute to

the most popular things in America and Japan at the time, which he

determined were Star Wars and Dragonball Z, respectively. Hence why

Sonic collects seven Chaos Emeralds to transform into a golden,

super-powered state, and why Eggman/Robotnik's latest creation is the

planet-like Death Egg. I'm not completely sure if that's a true

story, but it sounds credible.

The

point is that both series have had such a – what? Oh, you think

Gundam's not that important because Dragonball Z beat it out for a

reference in Sonic 2? Go plan a day trip to Odaiba, tell me if you

see anything interesting.

Close

to 40 years later, both Gundam and Star Wars are huge, at least in

their own countries. In case you forgot, The Force Awakens has just

dropped. 2015 saw the beginning of a new Gundam continuity, the

Iron-Blooded Orphans, which I haven't watched yet but is most likely

far less silly than the English title makes it sound. Both have been

the mother of sprawling franchises encompassing everything from

physical toys, books, comic books, video games, all kinds of shit.

Merchandising

“Lucas,” notes the Cracked article, “knew that he was, in part, making a series of toy commercials.” Once you

see it, you can't unsee it. Why are there so many variations of

Stormtrooper? Because then you can make a separate action figure for

each of them. Ayla Secura gets an action figure. Lando's co-pilot

gets an action figure. You can buy a goddamn Lego Death Star. The

Expanded Universe is/was so successful because it explores

intersting, in-depth stories within a compelling universe, but also

because it allows for a nearly limitless number of concurrently

developed products, with a huge install base, across every creative

medium known to man. They had these novels about Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan

pre-Phantom Menace, I thought they were just about the pinnacle of

literature when I was a little kid. RIP Expanded Universe.

“Lucas,” notes the Cracked article, “knew that he was, in part, making a series of toy commercials.” Once you

see it, you can't unsee it. Why are there so many variations of

Stormtrooper? Because then you can make a separate action figure for

each of them. Ayla Secura gets an action figure. Lando's co-pilot

gets an action figure. You can buy a goddamn Lego Death Star. The

Expanded Universe is/was so successful because it explores

intersting, in-depth stories within a compelling universe, but also

because it allows for a nearly limitless number of concurrently

developed products, with a huge install base, across every creative

medium known to man. They had these novels about Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan

pre-Phantom Menace, I thought they were just about the pinnacle of

literature when I was a little kid. RIP Expanded Universe. |

| GAT-X131 Calamity Gundam |

Now

Gundam is an interesting case, it wasn't designed with the

possibility of merchandise in mind, rather the プラモデル

plastic models were

designed first, and then

Tomino was called in to create the anime in order to market the toys.

When I first found out that Calamity from Seed was originally

supposed to be 1.5 times the size of a regular Gundam, but this was

changed because it would mean the scale model would have to be bigger

and thus more expensive, it absolutely blew my mind that something so

seemingly trivial could actually affect, no, constrict the creator's

vision. Of course, back then I also didn't know that a lot of the

best moments in movies were born from blind chance, that the stories

and settings of video games are crafted in response to the gameplay

mechanics and not the other way around, etc. Well, I was a child.

Which,

while I'm on the topic, is why it always amuses/frustrates me when

people complain that in making the prequels, George Lucas took Star

Wars and “made it for children.” Uh, have you fucking seen

the first three movies? THEY ARE

FOR CHILDREN. Look at Luke – he is a hero made for children. His

robot buddies are hand-made for children. And I'm sorry for treading

well-trodden ground, but come the fuck on:

Star

Wars is for children and always has been. And actually, so is Gundam.

It's sophisticated enough that you can see it for the first time as

an adult and still appreciate it, but let's be realistic, here, we're

talking about giant robots fighting each other. It's only that Japan

is a little less moralistic about its entertainment and coddles its

youth a little less. (Broad strokes. Obviously.)

Themes

|

| Char Aznable, fan favourite and one of the key characters of Gundam's "Universal Century" continunity |

Psych! The two couldn't be

farther apart. Gundam tells a nuanced anti-war tale in which there

are no clear good guys and bad guys; the antagonists in the first

series, the Principality of Zeon, want nothing more than independence

from the oppressive Earth Federation (and I spent much of the series

trying to figure out why the Federation didn't just give it to them).

Later series continue the story from their perspective. As things

develop, Mobile Suit Gundam scratches topics such as ecology (decades

before An Inconvenient Truth) and transhumanism. Star Wars,

meanwhile, is about how war is awesome, violence solves every

problem, the good guys not only always win but always survive, and

your enemies are all irredeemably evil.

Hero's

Journey?

You

could say that both Luke Skywalker and Amuro Rei follow a fairly

typical Hero's Journey, one of the recognized plot structures in

literature. Luke has humble beginnings (a moisture farm), gradually

comes into his abilities, and finally destroys the Death Star in the

climactic action sequence. It works even better on a trilogy-wide

scale, with blind luck leading the way to victory in A New Hope, Luke

screwing up and battling his inner demons in The Empire Strikes Back,

and emerging in Return of the Jedi as a confident, skilled combatant.

|

| Source. |

Similarly,

civilian teenager Amuro Rei is thrust into a combat role by

circumstances, and initially depends heavily on the capabilities of

his machine to achieve victory. Understandably, he develops (a fairly

believable depiction of) PTSD after a few battles, stops eating and

sleeping properly, and lashes out at the people trying to help him,

including his closest friend. At one point he even deserts his ship,

White Base, and absconds with the Gundam, which is military property

in the first place. Eventually he comes to terms with his fear,

achieves his potential, and becomes a truly skilled pilot bent on

protecting White Base and its inhabitants.

Of

course, I'm not sure this actually says anything substantial about

these two series. It probably just indicates that the Hero's Journey

is a good fit for a space opera. Which I guess is interesting in

itself, actually.

Accidental

retro-futurism

This

is a common pitfall of science fiction: By the time the real world

has caught up chronologically with the one you've created, it may

have actually surpassed the technology you were envisioning, or gone

off in a completely different direction. Early cyberpunk had

conceived of the Internet before the Internet was the Internet, but

it didn't occur to people back in the 80's that we would eventually

be able to access it wirelessly.

|

| "These days its design seems completely inadequate." Source. |

Again,

even today I find Mobile Suit Gundam relevant and immensely

enjoyable, but one does notice the occasioanl hiccough in

technological progress. I think this is most noticeable in the

viewscreens used by crewmen on White Base and in their mobile suit

cockpits, which is to say they look like an old TV your father has

stored in his basement because he hasn't bothered to throw it away

yet, not like modern monitors and certainly not like anything we'll

have by the time we're living on the moon.

Meanwhile,

control panels on the shiny, just-finished Death Star look as though

they're best suited for operating a Magnavox Intellivision.

|

| Cutting-edge computer technology in the world of Fallout. |

This

can injure suspension of disbelief, but I actually really dig this.

It's kind of like a fingerprint left on a work by the era in which it

was created. You can always think of it as an alternate timeline,

like in Fallout, where humanity pursued nuclear technology instead of

computer technology, so that even computers manufactured circa 2077

intentionally look like they came out of 1950.

Destruction!

The

Death Star destroying Alderaan is the cayalyst for sections of plot

in A New Hope. Mobile Suit Gundam kicks off with the destruction of

the protagonist's home, the space colony Side 7. Huh.

Laser

swords

Lightsabre

– beam sabre. Even the names are similar.

If

there's one thing East and West could agree on in the 1970s, it was

that laser swords are just plain cool. Or “totally radical,” I

guess.

But

all of this pales in comparison to...

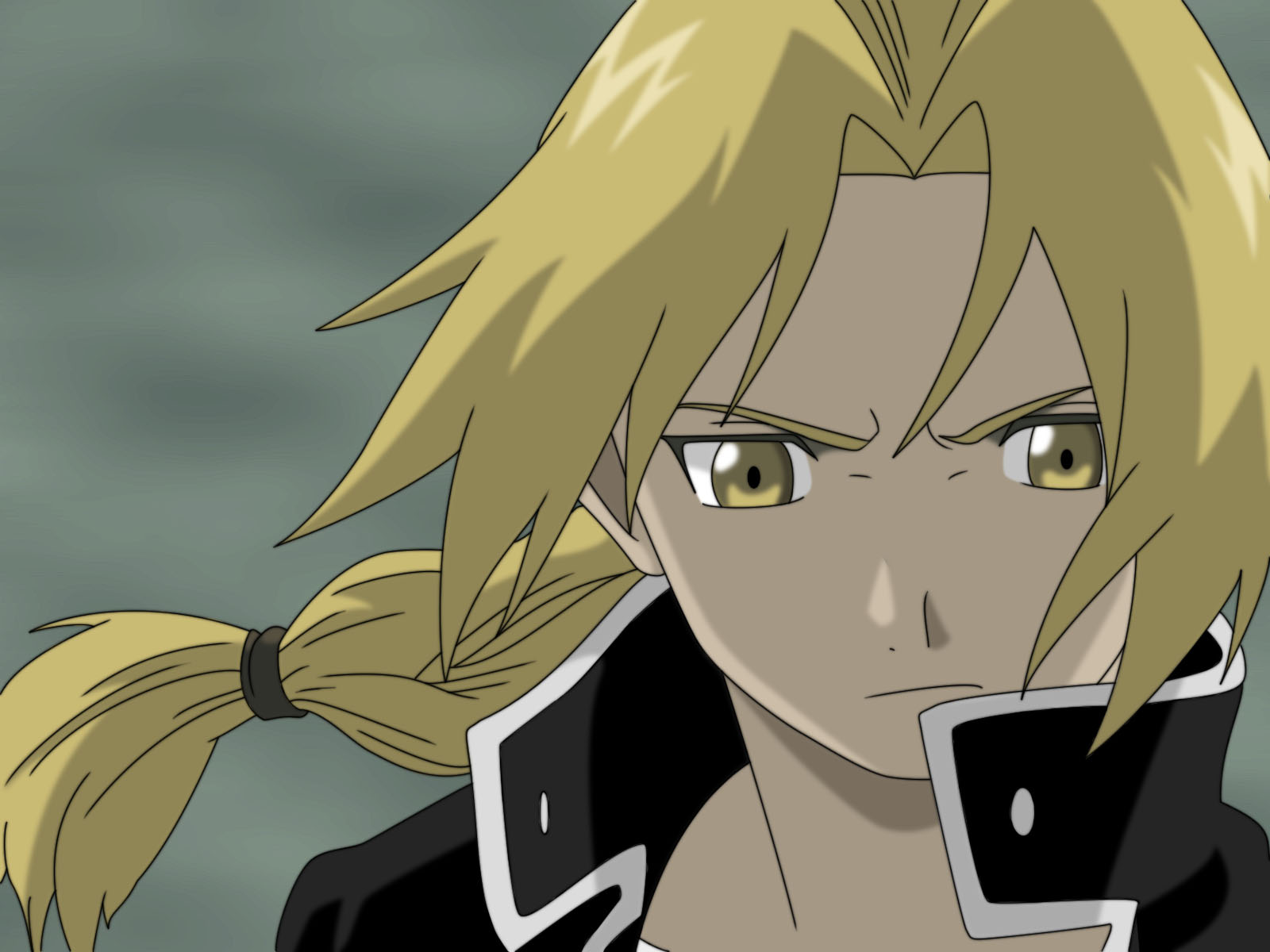

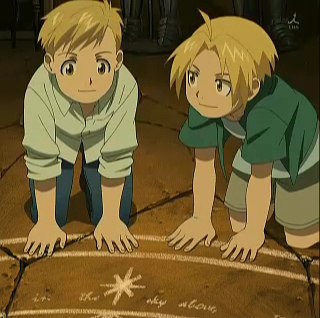

Amateur

mechanics

As

a young boy, Anakin Skywalker built C-3PO...

...and

as a budding scientific prodigy, Amuro Rei created the purely

decorative robot Haro.

Anakin,

of course, becomes Darth Vader. And in some Gundam series, Amuro

occupies the role of villain.

Coincidence?

The crossover section of Fanfiction.com thinks not.

.jpg)